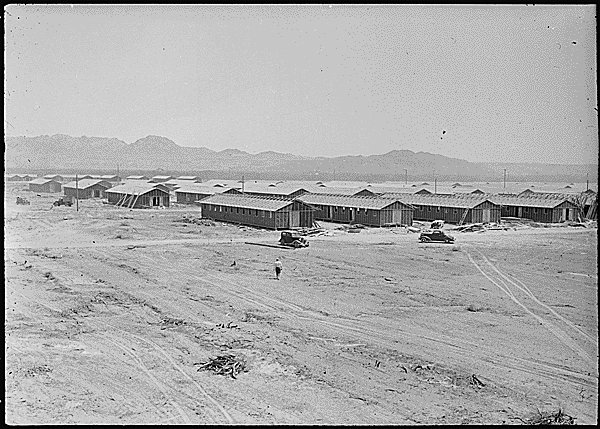

Poston Camp #1 in April, 1942, just before the first internees arrived

Today the road through Arizona’s Parker Valley runs arrow-straight between flat green rectangles of alfalfa. Shimmering irrigation ditches carry water to them from the nearby Colorado River, the boundary between Arizona and California. Mountains hem the valley on either side.

This part of Arizona is verdant now, but sixty years ago, it was a desolate desert reservation where Mohave and Chemeheuvi Indians lived in poverty. There were too few of them for the government to allocate funds to build irrigation canals so they could farm their barren lands.

Then, when war-time hysteria forced Japanese-Americans from their West Coast homes and businesses, the Poston Relocation Center was hastily thrown up on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. Officials of the Bureau of Indian Affairs saw an opportunity to bring in money from the War Department budget to make improvements and develop agricultural land. They also saw the advantage of thousands of “volunteers” to do the work, who could remain after the war and swell the reservation’s permanent population. The Tribal Council refused to be part of this plan, having themselves been “relocated” and forced to leave their homes and lands, but the BIA overrode the council.

Starting in April, 1942, more than seventeen thousand Japanese-Americans were brought to the outpost at Poston, where they were crowded together in unfinished board-and-tarpaper barracks, twenty feet by one hundred feet. Depending upon the number of people per family, up to four families were assigned to each building.

Actually, three complexes lay several miles apart, unofficially named "Roasten," "Toasten," and "Dustin" by their residents. Poston was not only the largest of the ten Western internment camps, it was also the hottest. Desert temperatures climbed to 115 degrees in the summer, exacerbated by humidity from the nearby Colorado River.

When the first evacuees arrived, however, heat was not the problem. Winter days were cool, the nights cold, and stoves had not yet been installed in the barracks. Winds stirred up blinding dust storms and whistled through the walls and floorboards. Sometimes torrential downpours turned the dirt streets and walkways into quagmires.

Why were Japanese-Americans subjected to such treatment?

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, people along the West Coast panicked. Some thought that every person of Japanese heritage had the potential of being a spy - or worse. Soon, community leaders began to agitate for their removal.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order authorized the establishment of zones from which anybody could be excluded. Immediately afterward, the evacuation and internment of 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry began on the West Coast. Those sent to Poston came mostly from Southern California.

During their three years of internment, the Japanese-Americans, many of whom were American-born and citizens, were forced to do the backbreaking work of building a working canal system, clearing fields, making their own adobe bricks for school buildings, and raising crops, pigs, and chickens for their own use. They established their own library, hospital, and other necessities. They even had a factory where they made camouflage netting for the war effort.

While their families attempted to continue life in as normal a fashion as possible, more than twelve hundred men and women from Poston served with the United States military forces. Of the 117 casualties, twenty-five soldiers died for their country.

Those twenty-five, and the other internees who suffered at the hands of their own country at Poston, are honored with a memorial near the site of the camp. Very little else remains to tell the story of their presence there, although in a way, the miles and miles of emerald alfalfa fields are a legacy. When the war ended and the evacuees were allowed to return to homes and businesses that in many cases no longer existed, the government lured members of the Hopi and Navajo tribes to the reservation with promises of good farming, running water, and other improvements to their lives.

Dennis Patch, a council member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes, grew up in a house that used to be one of the barracks. He said of the Japanese, “They built the schools here, they built the roads here, they developed the acreage into fields here, they brought the power down the center of the reservation. So up until that time, we as Native people were without running water, restroom facilities, without electricity. From their suffering, we gained a lot.”

As one stands at the Poston monument and ponders the story, one must ask, “Was the suffering worth it for America?” By the end of the war, only ten people in the entire country had been convicted of spying for Japan.

And all of them were white.

|

| Those from Poston who fought and died for America |

|

| Alfalfa bales and fields, looking west from the Poston Monument toward the Colorado River. |

Oh, Joan, this is a sad, sad story. You've told it beautifully, but I can hardly believe what panic can do to a nation. Such suffering, just for being born Japanese and living in the US. Thank you for telling a story we should never forget, a story that should never have happened.

ReplyDelete